This is it! The last author interview I did for The Bestseller Experiment podcast has been released and it’s with the brilliant Jacqueline O’Mahony and we discuss stuff like coming up with the title before the book, writing about ‘intangible things’, writing about tragedies like the Great Famine, winning awards at a young age, and the excellent advice, “Keep writing and something will come.” Enjoy!

Tag: writing tips

Speedy First Drafts with Rachel Lynch

I recorded this fun interview with bestselling author Rachel Lynch before I left the podcast at the end of 2023 (I think there’s one more in the vaults to be released!). We chat about how she can bang out a first draft in six weeks, writing gripping openings, making characters relatable, researching PTSD, writing about the super rich and a ton more…

Words To Cut To Make Your Prose More Punchy

Want to make your prose more punchy? Try cutting a few of those filler and filter words. Note: these aren’t hard and fast rules. Of course you can use adjectives and adverbs whenever you like. But if you’re editing, it’s not a bad idea to trim as many as possible.

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello folks. Want to make your prose a little more punchy? When editing, look for those adjectives and adverbs that can really make your writing drag. All those filler and filter words. Find them and get rid of them. For example… Deep breath… “Thought”, “touched”, “saw”, “he saw”, “they saw”, “just”, “heard”, “he heard”, “they heard”, “she heard”… “Decided”, “knew”, “noticed”, “realised”, “watched”, “wondered”, “seemed”, “seems”. That’s one of mine. “Looked”. That’s another one of mine.

“He looked”, “she looked”. “Could”, “to be able to”, yeesh. “Noted”. “Rather”, “quite”, “somewhat”, “somehow”. Although I think these are OK in dialogue, if used sparingly. “Feel”. “Felt”. Now this… this one always starts alarm bells ringing. Don’t just tell the reader that Bob is feeling angry. Try and describe his rage in a way that is unique to Bob. Which is easier said than done, of course. But no one said this would be easy. “And then” — paired together. Cut one or the other. “Had”. If you have two hads in the sentence, one of them has to go. Hads: two hads together… “had had”, which does happen. See if there’s a better way of writing around that. You might have to completely rethink the sentence. “He looks”, “she looks”. “He turned to her and said”, “she turned”, “they turned”… All this turning can make the reader feel dizzy and you can have whole conversations with people turning around and it goes absolutely nowhere. “Supposed”. “Appeared to be”.

“Apparently”. All of these can be weak and they can make your characters feel passive. If you’re writing the first person, these filter words can be doubly harmful. So… “I turned and looked up and saw the elephant raise its foot to squish me” is, well, it’s fine. “The elephant raised its foot to squish me” is a lot more direct. Keep those physical movements to a minimum. All that turning, twisting, looking… Give the reader just enough to animate the action in their own head. You’re not choreographing a musical.

So when you’re editing, look out for these filter words. Do a “find and replace”. Most of the time you’re better off simply cutting them. Other times you might see an opportunity to replace them with something a little more dynamic. What I mean by that? Okay. Add a bit of movement or action or texture. Instead of the “look to”, “turn to”… have them raise their chin, look down their nose, scratch their ear, run their hands through their hair, drum their fingers nervously.

Action that underlines what the character is trying to say or might be thinking. I find it useful sometimes to act the scene out. We’re all writers, spending far too long sitting on our backsides, so a little exercise won’t do us any harm. Get up, move about, film it, film yourself. No one ever needs to see it but you. But seriously, most of the time just cut the buggers. You’re better off without them. Of course there are exceptions. Sometimes we need these words to add clarity to a sentence, but too often I find myself relying on them when I should be trying to be a bit more zippy with my prose.

But hey, that’s editing is all about. Hope you found that useful. Until next time. Happy writing.

Five Tips for Writing Exposition

Here are five tips for writing exposition without getting bogged down in, well, exposition…

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello, folks, let’s talk about exposition. I’ve got to the bit in my book where my protagonist figures out what the villain is up to and there’s a ticking clock and she has to stop him before everything goes horribly wrong. Very much that tipping point from Act two into Act three. See an earlier video for tips on tipping points…

The great danger here is that this could turn into nothing more than a big dollop of exposition, also known, delightfully, as an info dump.

You know those moments in the movies where the villain reveals their evil plan, and this is so common that it’s become a trope in itself. There’s a lovely moment in The Incredibles where Syndrome says, “You caught me monologuing”. Basically, we’re talking about exposition. And in this specific case, how will the villain reveal their dastardly plan unless they tell the hero about it? Now, at this point in the story, the exposition is coming in late. As I said, the pivot between the second and third act, which is to my advantage, because if if you haven’t already, you can go back and leave clues for your hero and the reader to piece together what the evil scheme is, or if you want to invert that idea, your hero can think that they know what the plan is…

And then the villain can reveal a wicked, additional twist that they can take great glee in revealing. I think that’s what’s going to happen in my story. In the meantime, here are five tips for writing exposition; One: Have someone get it wrong. There’s a great moment at the start of Raiders of the Lost Ark where the two Secret Service guys come to Indiana Jones and tell him about the Staff of Ra, Abner Ravenwood, and something called the Lost Ark. And it becomes clear that they haven’t got the first clue what they’re talking about.

So Indy corrects their mistakes. This is such an effective way of getting exposition across that we, the viewer, hardly notice. It not only is Indy’s enthusiasm for the subject infectious, but it also gives him agency, and proves to us and the Secret Service men that he is the right man for the job. It’s a great subversion of an old trope because we’re so used to seeing James Bond stepping into M’s office and being told what the mission is, and it can be very passive with a big info dump. But this is a much, much better way of doing it. Two: Dramatise it. As with any essential bit of story information, it will always stick in the reader’s mind if you can dramatise it. Don’t tell me that your hero is a witch. Show me the hero doing some magic and include a few telling details. Is she skilled or does she need more experience and practise? Does she work alone or with others?

Does she use magic compassionately or for her own gain? By creating a bit of action and drama you can reveal so much more about a character than just having someone tell us. This can also be applied to a character revealing a bit about their past. Don’t just have them tell us. Show it in a widescreen, full-colour flashback, or a dream, or a crystal ball. Any bit of drama will be better than a dry retelling. Three: Do it with style.

OK, hands up. There are times when you kind of have to just tell the reader, or viewer, a bit of essential information. So if you have to do it, do it with style. Think of the opening crawl of Star Wars. Lucas pinched that from the old Flash Gordon serials, which had to bring the cinemagoers up to speed in just a few seconds… Or sing it in a song, interpretive dance, beat poetry, or have them tell a story with the kind of zingy and engaging dialogue used by the likes of Quentin Tarantino, David Mamet, Victoria Wood, Nora Ephron, Tina Fey, Shakespeare.

You get the idea if you’re going to tell it, make it good. Really good. I mean, extraordinarily good. No pressure. Four: Parse it out. Don’t feel the need to unload it all at once. Think about what the reader needs to know and when. Your antagonist might be a spy, a Nazi, a sous chef and an expert in kung fu. But that doesn’t mean we need to know all this when they’re first mentioned. Have some fun in revealing these nuggets when — and this is the important bit — when they can have the most impact on the story and the reader. To quote Billy Wilder, “Always allow the audience to add two plus two and they’ll love you forever.” Five: “Or… just don’t bother. You know, I’m old enough to remember seeing the first Star Wars, and not knowing what the Clone Wars were, why Darth Vader was in that suit, or even if Stormtroopers were real people or robots. And it didn’t matter one little bit. You’ll be amazed at how little some exposition matters. And as for BackStory, I’m going to let you into a little secret…

There’s no such thing as back story. There’s the story you’re telling and that’s it. The reader doesn’t care what happened before or after unless it directly affects what you’re telling them now. And if it does, then it will be in this story. If it doesn’t, don’t bore them with it. Tell one story and tell it well. Don’t weigh it down with a bunch of digressions. Honestly, I blame Marvel. Ooh, controversial. Right. Well, I hope that was helpful.

Any questions? Pop them below or drop me a line. Until next time, Happy Writing.

Here’s One Way To Write A First Draft

I’ve been working on a new way of writing the first draft of my novel. And it’s been working really well… so far…

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello, folks. Apologies for the hair. Still in lockdown and two weeks till I get a haircut, so this is going to get worse before it gets better. Anyway, I’m working on the first draft of Skyclad, the third Witches of Woodville book.

Regulars will know that I used to be a big outliner when it came to writing, but I’m becoming more and more of a pantser or discovery writer, whatever you want to call it.

That is, I’m making it up as I go along. Well, sort of. I do have a rough idea of where I’m going and I know how I want the story to end. And I have a few key notes on a few key moments, but I thought you might be interested to know how I’m working with this one. Again, regulars might know that I have a different notebook dedicated to each project. Here’s the one for Book Three of the witches of Woodville, Skyclad.

This was bought at the National Trust Gift Shop at the White Cliffs of Dover, which is a little clue as to where some of the book will take place. What I’ve taken to doing with this story is switching from day to day between paper — the notebook — and the screen — the laptop — and it’s really working for me. So to give you some idea… On, say, Monday, I will start noodling ideas for what happens next in the story in The Notebook.

So here I’ve written in big letters, “How can the Poltergeist exorcism go wrong?” Slight spoiler, but it’s the opening scene. I’ve made notes on what can happen in that scene and they are imperfect notes. I’ve given myself permission to wander off, and noodle and try different scenarios, and scribble stuff out, and put other things in boxes and underline them, and highlight them. And what I find is that by the end of the writing session, I have a really good idea of how that chapter pans out.

The level of detail varies from session to session. But the next day, Tuesday, when I open up the laptop, I’m not victim to the tyranny of the blinking cursor. You know that feeling when you look at a blank page of Word or Scrivener that bastard cursor is flashing at you, “Go on, write something. What are you waiting for? Call yourself a writer?” Well, now I just go to my notes and start typing, and before I know it I’m up and running. I used the less formalised version of this with The Crow Folk and the second book, Babes in the Wood, available to pre-order now.

And it worked really well. So this is an evolution of that. A few caveats. I’m only 10,000 words into this novel and, in my experience, openings are pretty easy when compared to the rest of the book… not least the middle section, which can lead to much wailing and gnashing of teeth. So I’ll check in with this in about a month’s time and see if I’m feeling quite so smug still. Also, I’m writing the third book in a series.

I know the characters and situations really well. I have a very good idea of how people will react when presented with challenges. And that makes a writer’s life much, much easier and makes me wonder why it’s taken me so long to write a series. This is so much fun. Anyway, I hope you found that helpful. How is your writing going? Does this sort of method work for you? Pop a comment below or drop me a line. In the meantime, happy writing.

Where I got the idea for The Crow Folk

We had a special episode of the Bestseller Experiment this week and Mark Desvaux asked me a bunch of listener questions about The Crow Folk. I’ve broken them up into short videos, and in this first episode I talk about how the idea developed from a contemporary TV pilot into the Second World War novel that’s out now.

You can listen to the whole podcast episode here.

Discover more about the Crow Folk and the Witches of Woodville here.

TRANSCRIPT:

MARK STAY: Hello folks, it’s here! Look! Finished, gorgeous. Thanks to everyone who bought the book, read the book, said lovely things about the book, a huge thank you to all of you. It really means a lot. What you’re going to see today… We had a special episode of The Bestseller Experiment where I answered a whole bunch of listener questions and rather than one big lump of video I’m going to do them in little chunks over time, in more digestible chunks. So the first of these, people ask me where I got the idea from and how it developed. And this has been in development for some time. Be warned: this video contains gratuitous bellringing.

MARK DESVAUX: But let’s let’s dive in because there’s a lot there’s a lot of things people want to know about this book. And the first thing the first question is from Jan Carr, and Jan asks, where did you get your idea from?

MS: Classic, classic, and just to reassure listeners, so I’m going to try and make the answers as helpful for writers as possible, and it’s not just going to be me blowing smoke up my own bum for an hour, I mean, maybe for just forty five minutes. So hopefully we’ll get some insight into working with agents, editors, development, ideas, writing for series historical fiction, stuff like that. So Chris asked the same question. Chris Lowenstein: Where did you get the idea? Matt says, of all the story ideas you likely had before you started this book, why did you choose this one? Tanya says, How do you decide if it’s a book or TV thing? What made you a great idea for a novel? A lot of variations on that. But here’s the thing. I’ve got files going back on this idea going all the way back to 2008. So it’s… and it probably dates to before that. I mean, this has been mulling around for a long, long time. And it did, weirdly, it started out as a TV idea, but it was very different.

First of all, I think the big problem with it was I had the point of view completely wrong, and it only took me about 10 years to figure that out. And the period was wrong too, because it was contemporary. Set in the here and now. So a few things had to change to sort of make the idea fall into place. And for me, it really started getting momentum in its current form when we were visiting friends in Chiddingtone in Sussex. I don’t know if you’ve ever been to Chiddingstone. It’s on the border of Sussex and Kent. And it is your archetypal English village. It’s absolutely gorgeous. Weirdly, I work with the chap who lives there called Mark Streatfeild, who is kind of Lord of the Manor at Chiddingstone castle. He’s related to Noel Streatfeild who wrote Ballet Shoes. And they have… The family have their own coat of arms and everything. And Claire was down there, bellringing And while she was ringing, me and the kids sat outside a pub and the kids challenged me to come up with an idea for Doctor Who. And I don’t know if you’ve ever heard a whole session of bellringing? But they do something at the end. They ring down the bells because the bells have to be put in a position where they kind of put up and then they’re rung down and something happens to the bells, the bells and ding, ding, ding, ding, ding. They start ringing very, very closely together, really, really closely together. And it creates this incredible sound, an absolutely incredible sound. It’s like the lost chord from the beginning of the universe. It just creates this incredible magical hum and… And I got something from that I thought that could be that could be something magical, but that’s a good MacGuffin. I could use that. And of course, we’ve been using bells to fight off evil since time began. So bells…. Bells was something… Going to be very important and also Claire hosts… The bellringers will go on journeys. They’ll go from Surrey to Kent and back for the day back or whatever. And they they use us as a base for a couple of days. So sort of twice a day they come back and I’d have to make 40 cups of tea and then double up 40 lots of sandwiches or whatever. And I joked to them, oh, this is just after The End of Magic came out. I joked that I would make bellringers the heroes in my next book. So so the whole bell ringing MacGuffin was coming together. And it does play a really important part in The Crow Folk and then the time period thing put it into place, because it was still a TV idea. My TV agent, my script agent said, why don’t you set it… Instead of making it contemporary, why don’t you set it in the Second World War? Because that period England… Downton Abbey is an easier sell to Americans and overseas people than contemporary England. And that just… Another sort of thing sorted into place. Okay, great: World War Two and… I’ve moved to Kent. Moving here made a big, big difference because… Moving to the country made a big difference. And World War Two, I mean, it happened here with the Battle of Britain right above our heads. So moving here made all the difference.

MD: I got to say…

MS: Slotted into place and then.

MD: I was going to say, yes, that’s kind of like and it’s an extreme case, isn’t it, of a book research is to actually leave leave the suburbs of London and buy a house and therefore you’ve immersed yourself in it. Must have changed a lot because immersing yourself in kind of a village kind of environment must have given you an amazing kind of sense of backdrop for the book. Right?

MS: Completely. Completely. I mean, one of the nice notes I’ve got from someone who read the book said they said you write nature really well, and it’s just being here. You become a lot more aware of the nature and the surroundings. And then the big thing that clicked into places I got the POV right. In and the original version had been the monster’s POV. With this, I created a created a character called Faye Bright. She’s this young girl. She’s your classic, you know, hero… ingenue, kind of, you know, of character. And it all kind of started to click into place. And going back to I think it was Matt who said, why choose this one? It was just the idea that just would not go away. And I couldn’t figure out why… I’d write other things. And whenever I finish those things, I came back and this idea just kept coming back: a magical wood, a village. And, you know, the other thing is I knew this had series potential, you know, that endless well of story. And for years I’ve been trying to think of a series idea, something I could come back to. Well, could it be a science fiction idea? Fantasy idea, what have you? And this it all clicked into place about a character that was able to grow with the series. You know, she’s 17 in this book, but she’ll grow as it goes on. And it just took a really, really long time to see what was right in front of me. But, yeah, that’s a very, very long answer. But it had a very, very long gestation. It’s been around for 13 years. And ten of those it was kind of swimming about and it was completely wrong. So if anyone out there is thinking, you know, I’ve got this idea and it just won’t gel, just be patient. Just if it keeps coming back, if it keeps nagging you, there’s something in there. There’s there’s gold in them thar hills. And you just have to have the tenacity to hang in there because eventually it will reveal itself.

MD: I think it’s a brilliant, brilliant testament really to that idea. And we often call it signposting where you get to you know, you get an opportunity in life where you can start something new or you can try something and you look at the signposts and the different things that you could do at that point in your life. And if there’s a signpost is always there, it’s always like this is this I’m not going away. I’m not leaving you. If you see that enough times, you really have to follow up. And it sounds like intuitively you went right now. But it’s also about timing, is it? Well, I mean, you couldn’t have written this book five, ten years ago, right?

MS: Well, I did. I did write the book. I mean, that’s the thing. I mean, we’ve got questions about development later on. I finished many, many drafts of the wrong book, you know, that eventually kind of and scripts, you know, TV pilot scripts, feature length scripts that I got to the end of. And they still didn’t work. So, you know, it’s I did write it, but it was it was just wrong. It was it was wrong, wrong, wrong era and not the right character for you to write the right book as well.

If you enjoyed that, folks, there’s more to come. I’m going to be talking about future episodes, things like development, the writing process, writing historical language, historical dialogue and comparing my experiences in crowdfunding and indie publishing and traditional publishing, all that good stuff. So subscribe and don’t miss an episode. See you soon. And happy writing.

Plotting vs Pantsing

When you write, do you prefer to outline beforehand? Or write by the seat of your pants?

I go for a walk without a map and discuss plotting versus pantsing. Beware: heavy-handed metaphors ahead!

TRANSCRIPT:

Hello folks, Mark Stay here. I’m on a walk today.

One of the things I want to talk about today is plotting versus pantsing. Something that’s been on my mind quite a bit. And I’m on a walk because, and you should be aware of this, there are some heavy-handed metaphors on their way, because I’m going on this journey today and I have no idea where I’m going. Hey, hey, hey. Plotting, pantsing, eh?! Anyway, so let’s get on with it.

So, yeah , let’s define some terms first. So, a plotter is someone who outlines before they write. A pantser is somebody who writes by the seat of their pants. And this term was completely new to me before I started the podcast I hadn’t heard of it before. I think it’s an Americanism, frankly. But yeah, it kind of makes sense. You know, there are people who make it up as they go along. And I’ll be honest, I was, uh… the idea of that always kind of terrified me and I was always a very big outliner. And anyone who’s listened to the bestseller experiment podcast will know that I got quite a bollocking for that from Ben Aaronovitch, because my outline was, well, for Back to Reality that I’d written with Mark Desvaux was some 50-odd-thousand words long. Which is, to be fair, is quite a lot. And it was quite a wake-up call for me. In my defence my background’s in screenwriting and in screenwriting, you have to outline everything because you need to serve stuff up to directors and producers, pitching stuff that you haven’t actually written yet. I’ve done it. Just this week, I put together a 10-page outline for a TV show for the director to see. Now, I’d rather write that 10-page outline than a 50-page pilot show that he then doesn’t like at all, you know, so it makes a lot of sense to do that, certainly in the film world. And certainly if you have a deal with a publisher, they’re gonna ask to see synopses upfront, but not big ones, usually just three paragraphs tops, usually. So, you know, you do have to outline a bit and certainly Ben Aaronovitch says he does, like, a page. You know, before he writes anything and other authors we’ve spoken to, people like Martina Cole, you know, they do a page. The important thing is they have an ending. They know where they’re going. They know where the protagonist is going. Anyway, back to me. and my fifty thousand word outline.

Ben’s bollocking was quite a wake up call because it made me think, actually should I really be… is this is the right way to do this? Is there a right way or wrong way to do this? So the book I’d been working on before the podcast that I put aside to write Back to Reality was my fantasy novel, The End of Magic, which I had outlined very, very heavily. You know, I had three plot strands going on and I needed to know where they were going. And I felt outlining would really, really help me. And I’d done it. I’d finished the draft before starting the podcast, put it away. And then sort of a year later, after we wrote Back to Reality, I picked it up again, had a look at it and realised two of the threads were fine, really, really good. There was one character that just wasn’t working. A character called Oskar, and he needed work. I had a choice, then. I could have sat down and outlined it very heavily. Or I could have pantsed it. Fly by the seat of my pants. Well, that’s what I did and I loved it. It was great. I mean, I had the safety mat in that I knew everything that was going on all around him, you know, I knew what’s happening with the other characters. I knew how the story was going to end. I had a very good idea of how I wanted his story to end. So I approached the rewrites of his chapters just with the attitude of “What happens next?” What can be the most interesting thing that happens to poor old Oskar? I made his life hell. Very difficult. And I loved it. I had a great experience. And what’s interesting is in a lot of the reviews, people single out Oskar’s thread as their favorite bit. So that was a lesson learned, you know, and I took that to heart. So when I started working on my next project, which was the Woodville books, I figured, you know what? Let’s pants this one. And I did.

The Witches of Woodville Books, starting with The Crow Folk. OK, I figured, you know what? Let’s pants these. A little bit of history on the books. I’d been writing them on and off for about ten years, basically as contemporary fiction set in the current day. You know, with magic and what have you. It just wasn’t working. And so I put them away and it was my TV agent who said, you know, why don’t you set them in the Second World War? He figured I could sell a TV series like that to the Americans. Much to his annoyance, probably, I started writing it as a book series. And it all clicked into place. But what I did was abandon any previous story ideas. I worked on the characters, particularly the character of Faye, and just figured where I wanted her to end up and headed towards that ending. So I did kind of a one-page outline and got to know Faye. I wrote the book up and around her. And I would ask the question, what happens next? How can I test her? How can I make life difficult for her? How will she recover? And pick herself up? And dust herself off and become a better person? And it was fun. It was really freeing.

The other habit I started was I got a notebook and at the end of my writing day, which is only a couple of hours each morning, I would write what happens next or write down sort of half baked ideas, “What happens next?” Or finish mid-sentence. And the old brain— Wow, look at this. The old brain would be ticking away. And I would usually have ideas at some point during the day. Send them to myself. And the next morning I knew what I was going to be writing. So, in a weird way I was still outlining. But just, you know, one nibble at a time. And it worked and it needed surprisingly few rewrites as well. Because that’s the thing with outlining. I think I always viewed it as a safety net. I always viewed it as that thing… How rude. I always viewed it as that thing of, you know, at least I know where I’m going. But, you know, I’ve been writing for so long now, I kind of know story structure. I kind of have a good idea of what should happen next. And then I heard on the Script Notes podcast, a brilliant talk by the screenwriter Craig Mazin, where he said what he uses is, he knows where he wants his character to end up. He kind of has his ending in place. And then he writes from the opposite of that, you know, so he knows how they’re going to change over the course of the story. So he says, whenever I got stuck, I would just think, OK, I’m going from “this” to “the opposite of this”. How is this chapter affecting that? How is my character changing in this part of the story? And it’s such a simple rule and it works. So I use that. And I’ve used it for the second book in the Woodville books, which I’ve just handed in to my agent. You know, that’s kind of been my method. But that’s not to say that I’ve abandoned plotting altogether. I have to do it with screenplays. It’s just like I said, I’ve just done a TV thing. So this idea that it needs to be an either/or thing is hooey. I think George R.R. Martin says, you know, writers are either architects or gardeners. You know, they build something or they let it grow organically. I don’t see why you can’t be an architect with a garden, frankly. Why the hell not? Yeah. By the way, this is where we shot the video for The Crow Folk. It’s changed a bit since the summer, hasn’t it? There’s normally a path here. These are new!

That’s not to poo poo people who outline, you know, outlining, I’ve done it and it’s been successful for me, you know, if that’s the way you do it, go for it. All power to you. But I don’t think you have to define yourself as one or the other. You know, allow your writing style to evolve over time, allow yourself the flexibility to change the outline, because, by all means, study the Hero’s Journey, Save the Cat, all of those seven point story things or whatever. Understanding structure is important. Definitely important because it allows you when you are stuck to maybe fix things. But what I would say is all those books, you know, on why Thelma and Louise and Silence of the Lambs is, you know, the greatest structured screenplay ever. They’re all done from a point of analysis. After the fact. The screenwriters weren’t thinking like that. You know, they were just thinking what happens next? And either through experience or their own insight, they were able to come up with great solutions. And believe me, they didn’t come up with it first time. They would have rewritten and rewritten until they got it right. See, don’t let anyone define what you should be as a writer. You have to figure it out for yourself. That takes time. It’s taken me over 20 years.

So here’s the heavy-handed metaphor bit. When I left the house this morning. I didn’t know which way I was going to walk. I knew that I was going for a walk, but I didn’t have a preplanned route. But I know the area really well. I didn’t realize it was going to be so muddy back there. But I got through it because I’ve been here before and I sort of know the way. Huh? I told you. It’s heavy-handed, didn’t I? I’m a writer. I do metaphors, me. Oh, yeah. But, you know, I’ve ended up here. I’m pretty happy with that. Yeah, it’s not bad. All things considered, at the end of it, I’m going to reward myself with a cup of tea, maybe a little cookie or something. Here we go. Till next time, happy writing. And if you get lost, don’t worry. There’s usually a path somewhere.

Five Tips For Writing Around A Day Job

Want to write a novel, but juggling a day job, commute and other such commitments? I’ve written novels and screenplays while shuttling back and forth to London, and here are five tips that helped me make the most of my limited time…

I’m Pantsing the Pants Off This (and Loving It)

Or, How I Learned to Write Without a Massive Outline

For as long as I’ve written, I’ve loved a good outline. It comes from my screenwriting where outlines are something of a necessity when dealing with agents, producers, directors, etc. They like to know what they’re getting for their money upfront and it’s not unusual for the writer to put together some kind of pitch, synopsis or beat-by-beat outline ahead of actually writing the thing.

I’ve done the same with my novels. I’ve always liked to write a thorough chapter-by-chapter outline — a clear roadmap, because I’d hate to be halfway through a hundred-thousand word novel and not have a clue what happens next, or discover a massive plot hole. If you’re a regular listener of the Bestseller Experiment podcast, you’ll know that it got me a proper bollocking from that nice Mr Ben Aaronovitch (skip to about 26 minutes in…).

Since the Great Bollocking I’ve had two novels published, Back to Reality and The End of Magic, both heavily outlined and people seem to like them. But… both were well in progress when Ben gave us an earful, so I figured what the hell, I should just finish what I started with them.

I listen back to our old podcasts fairly regularly. Not out of any vanity, but I really do believe we got tons of amazing evergreen advice from some of the best authors in the business and it would be daft to ignore them. One thing that became clear is there’s no single method of writing a novel. Lots of writers love to outline, plenty of them are pantsers (writing by the seat of their pants… a term I had not heard before starting the podcast), many do a little of both. There’s no definite, step-right-this-way-to-success system. You have to figure out what works for you and build on that.

I was happy outlining, but I’ve prided myself on never writing anything the same way twice. Every time I start a project, it’s a little different and I learn something new. I figured it was time for a big change, so why not try and pants a full-length story?

But what about that fear of getting lost? Of getting halfway through a story and not knowing where to go next?

It was another podcast that had a nugget of advice that unlocked it for me. I’m a big fan of Scriptnotes, a podcast for screenwriters (and things that are interesting to screenwriters). In it, screenwriters John August (Big Fish) and Craig Mazin (Chernobyl) discuss craft and the industry, and I find it invaluable. Last summer (2019) they released an episode featuring just Craig who gave a talk that he’s given to screenwriters at festivals over the years.

It’s a brilliant episode, crammed with terrific advice. It’s behind a paywall now, but you can read a transcript of the full episode here.

The advice that stuck out for me was this…

“If you can write the story of your character as they grow from thinking “this” to “the opposite of this”… you will never ask what should happen next ever again.”

Craig Mazin, Scriptnotes, ep403, 41m 50s

A little lightbulb went off in my head. It was the same question I would ask myself while writing an outline anyway, so why not apply it to the blank page of a fresh draft? Would it be any different? Would it be any better?

I’ve been using and adapting this method for one screenplay (written on spec, no outline necessary) and one-and-a-bit novels and I’m loving it. I’ll start with a one-page outline, but with a bigger focus on character and theme. Who is this character? How will they change, and what’s stopping them from doing it? With those two polar opposites in mind, I rough out a very basic story and then start writing. It can be hard at first as you test the water. When I get stuck, I put the laptop aside and start scribbling in a notebook with Mazin’s advice in mind: What’s what the worst thing that can happen? What will stop this character from getting what they want? How will they overcome it?

If I can’t figure it out right away, I might stop writing altogether and get on with my day. More often than not I’ll have a solution come out of the blue while I’m washing dishes, in which case I dry my hands and email myself the note ready for the next day.

It’s working so far. The screenplay has a director and producer attached and looks like it’s a goer, and the one and a bit novels…? I’m hoping to have some good news about them soon.

I’m not saying this is going to work for everyone, but I’m enjoying living on the edge. If you’re a big outliner, why not give it a go? All you’ve got to lose is your word count…

10 Productivity Tips For Writers

On the most recent live show of the Bestseller Experiment podcast we got talking about how to make the most of your writing time. You can listen to the whole podcast here (where we also launch the BXP2020 challenge, which will make 2020 your best writing year!) and I’ve listed my top ten productivity tips below…

Procrastinate first

This may sound a little odd, but we all have our favourite forms of putting off writing, so why not just get them done and out of the way? Mine is social media. If you follow me on social media, you might notice that I’m busy first thing in the morning (breakfast), I might pop up for ten minutes or so mid-morning (tea break), then there’s lunch and then the evening when I’m done.

Diving into Twitter and Facebook first thing in the morning quenches any curiosity that there might be something more interesting going on in the world. I pop in, have a laugh (or get outraged), put it aside and then jump into the writing.

Close the door

The old advice from Stephen King. Most people think The Shining is about a writer battling his inner demons, but I reckon Jack just wants to make his daily wordcount and his wife and kid complaining about the terrors in the Overlook Hotel really isn’t helping the poor guy hit his targets.

Closing the door works. If you’re lucky enough to have a room of one’s own then use it, and make sure your family or flatmates know what it means: no knocking unless there’s a fire, nuclear war or similar*.

Before I was lucky enough to get a writing room, I used to write on my commute on a busy train. I used headphones to block out the world. If you’re a time poor writer — and who isn’t?! — you have to make the most of your writing time and any distraction can be detrimental to keeping your train of thought. Which brings me to…

*Unless they bring tea and biscuits. I can allow that occasionally.

Silence (or nature sounds)

I used to have specific music playlists for any writing project and I find these useful when I’m brainstorming ideas and trying to get into mood… But when I’m in the thick of a draft I now need complete silence. It might be a middle-age thing, it might be that I just need more brain capacity to concentrate on this stuff, but I can’t write now if the theme from The Witchfinder General is scratching at my brain.

When I’m travelling and using headphones I’ll use a nature sounds app. This blocks out extraneous noise and is far less distracting than music, though you if you find that you start getting annoyed by repetitive bird calls, then maybe switch to a white noise app.

Set targets

What are you actually going to do today? Is this a first draft and you’re hitting a word target? If it’s a screenplay, how many pages do you want to do today? If you’re editing, are you working on a particular chapter, character or thread? Whatever it is, set yourself a goal. Once you’ve hit it you can either smash through or, what the hell, take the rest of the day off and binge something on Netflix. One of the biggest lessons we’ve learned on the podcast is setting achievable goals is one of the biggest boosts to writing productivity.

It’s one of the reasons we launched this thing.

Know your arguments

It’s all very well splashing words onto the page, but what the hell are you actually saying? What is the point of this book? This character? This scene? And where are you in the story?

I always take a moment to figure out just where I am in the story. If my protagonist starts at A and ends up at Z, where am I in the alphabet of change? How is this scene helping them evolve and head towards that ending? What change is occurring through drama? In other words, how does this scene earn its place in the story? I find that once I have a clear idea of that, the rest comes relatively easily.

Make notes always

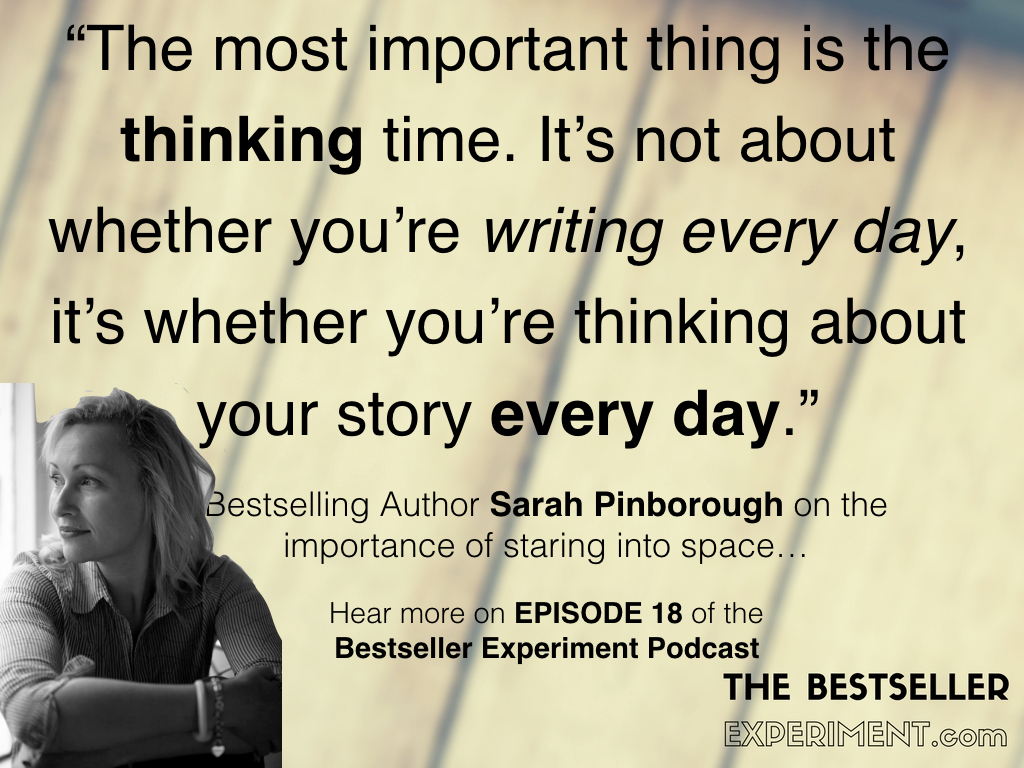

One of my favourite moments of the podcast is when Sarah Pinborough challenged the “Write every day” theory that we were really excited about.”That’s bollocks!” she said…

And she’s absolutely right. Keeping that story brain ticking over in the back of your mind is so important. But, if you’re like me, you have no idea when inspiration might strike. It’s usually at two in the morning, so I have a stack of Post-It notes by the bed, or I’ll be out for a walk and a story problem might solve itself and I end up sending myself an email on my phone before the thought it gone…

And that’s the dread thing. I know now that if I don’t make a note STRAIGHT AWAY, it’s gone. For good. Again, that might be a middle age thing, but it’s real. Always be ready to make notes wherever you are.

Change medium

I’m a pretty speedy typist. My dad used to be secretary of football referees association and I used to type up his handwritten notes for their newsletter on a second-hand fire-damaged BBC B computer, so I was a touch typist from about age eleven. The temptation for me is to stick to typing on a screen because it’s so fast, and that’s great when I’m on a roll, but when it comes to problem-solving you can’t beat pen and paper. There’s something about scribbling on a pad, or a scrap of paper, or on a whiteboard that fires up a whole new set of synapses in my noggin. I’m hearing a lot of writers are switching to dictation now that the tech is getting more reliable. I haven’t tried it yet, but watch this space.

Regular breaks

This might feel like more procrastination, but at my age I have to get off my arse every hour or so, if not more. If I’m working from home there’s always a bit of washing to put on, a dishwasher to empty, some vacuuming to do. Getting up and moving around gets my blood flowing and it’s a good way to let the brain take a breather, and it often leads to solutions to story problems. And of course nothing beats a good walk…

But doesn’t all that interruption break into my concentration…? Well, I have a thing for that too…

End mid-sentence

Whenever I take a break, and especially at the end of the day, I try to end either in mid-sentence or in the middle of an incomplete scene. This means that when I resume work I’m not faced with a blank page or fresh chapter to start. I just need to polish off what I was working on yesterday. I’ll often leave myself a note along the lines of, “You were thinking this, and this thing was going to happen next.” That’s usually all I need to get started and before I know it I’m up and running and ready to tackle the next chapter.

Similarly, if I ever get stuck I’ll go back and rewrite or edit the pages running up to the moment of stickiness. This run-up usually gives me the momentum I need to break through the sticky bit and keep going.

Prepare to change

Here’s the thing. What worked for me two years ago, doesn’t necessarily work for me now. I’ve never written a script or a book the same way twice. I’m always looking to shake things up. I think the day I think I’ve got it all figured out is the day to give it up.

Bonus tip: Back up your work

Every day. Back up your work to a dongle, a cloud, email yourself — whatever it takes to ensure that your magnum opus isn’t sat on a device that will inevitably crash and die. There’s no “maybe” about this. Tech dies every day and often without warning. Sometimes it’s unavoidable and that’s horrible, but you can and should take steps to avoid it.

The 3-2-1 back up rule is best: keep three copies of your data, two on different storage media and one off-site.

I hope this was helpful. We talk about this more on this episode of the Bestseller Experiment.

And do please leave your own tips and comments tips below…

Are you looking for feedback on your novel or screenplay? sending to agents? I offer all kinds of services for writers at all stages in their careers. There are more details here and get in touch now for a free ten minute Skype consultation and a quote.